A riveting new documentary tells the story of the biggest tech revolution of the 21st century. And it isn’t digital, it’s biological.

When Oscar and Emmy winner Adam Bolt directs a documentary in collaboration with a world-class writer-scientist team, and media icon Dan Rather backs the project as one of its executive producers, you can be pretty certain there is a story to tell – a significant story of far-reaching implications, and one that is told well. The documentary Human Nature is a provocative exploration of CRISPR, the scientific breakthrough which has given us unprecedented control over the basic building blocks of life.

After its recent world premiere at the SXSW Film Festival in Austin, Texas, the documentary is currently on the international festival circuit where it has already received numerous distinctions. On October 26, it will come to Paris in its only French screening currently scheduled. Other European screenings include Oslo, Norway on November 6 and London, UK on November 29.

Human Nature examines CRISPR through the eyes of the scientists who discovered it, the families it affects, and the bioengineers who are testing its limits. Gene-editing opens the door to curing diseases, reshaping the biosphere, and designing our own children. How will this new power change our relationship with nature? What will it mean for human evolution? Is that human intervention a good thing or does it contain inherent scientific or ethical risks? How far can Man morally go? Where is the limit you cannot overstep and who defines it?

To begin to answer these questions we must look back billions of years and peer into an uncertain future.

But first of all, what is CRISPR, in layman’s terms?

Unscientifically speaking, CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) is a protein which is often described as “molecular scissors”, or a “software” that can be programmed to find a very precise sequence in a DNA and to cut it. Human DNA contains over 3 billion letters in every single cell, and renews and repairs itself perpetually. During that process, copying errors can happen. CRISPR-Cas9 (to be exact) is a protein that allows scientists to make very precise changes exactly where needed. But how do you that with something that is 40,000 times smaller than a human hair?

CRISPR is in fact a natural process that humans learned to harness by studying how microorganisms use it to disable viruses in a very precise manner. “It became a household word in late 2012 and early 2013, after a series of papers showed that it could be used to precisely edit the DNA of humans, crops, animals, insects, you name it. It turned out to be an almost universal tool for gene editing. And then things started moving very quickly. Within a year, someone had used CRISPR to edit monkey embryos, and it was clear that it would soon be possible to do that in humans as well,” explains documentary director Adam Bolt.

And that has profound implications. Until very recently, genetic engineering in humans has been confined to what are called “somatic cells.” Most cells in your body are somatic cells—skin cells, blood cells, brain cells, etc. If the DNA in those cells is edited, that change is confined to that particular tissue. But the DNA of sperm, egg, or embryo cells are altered, that change is passed down to future generations. This is called germline editing, and it had never been possible in humans until CRISPR.

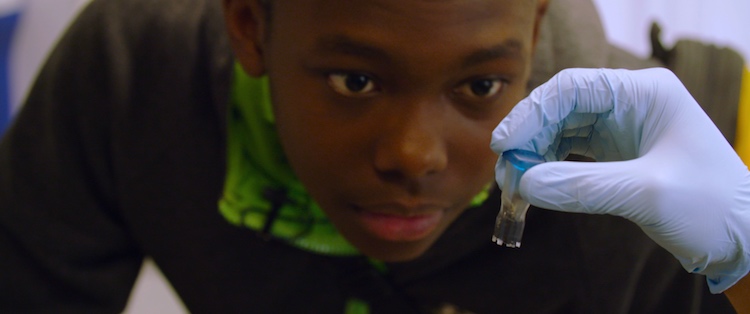

That “DNA hacking”, as some call it, is technologically doable is no longer a question. But in recent years, the science community has gone from potential to possibility in an unprecedented Brave New World scenario in unchartered waters. Human Nature takes a good look at the ramifications. Take for instance the case of David Sanchez, a teenager with sickle-cell disease. A cure is already being developed, which will bring help to hundreds of thousands … What about the 11-year-old with OCA2, a form of albinism? Should conditions like this be edited out of our genomes before birth? Where do we draw the line between disease and diversity?

There are justified clinical applications where the technology is a blessing, or at least ground for constructive social discourse.

But what if parents just request that their offspring should be much taller than themselves or have specific abilities? Maybe employers want to condition their staff to never need a break, or the military demands to make its soldiers immune to fear and pain? When Vladimir Putin is shown in the documentary discussing the engineering of flawless musicians or mathematicians and closes his remarks with “What I have said may be more terrifying than a nuclear bomb”, it might give cause for pause indeed.

Adam Bolt’s documentary examines these issues without prejudice and not without a sense of humour. What could be a rather dull topic for any non-scientist, suddenly comes to life through cases and narrative. But as Human Nature points out, we are at the end of the beginning, for better or for worse though it may be.

CRISPR is the brainchild of American biochemist and UC Berkeley professor Jennifer Doudna and French microbiologist Emmanuelle Charpentier, two outstanding scientists who pioneered this revolutionary biotechnological tool. The research team around these formidable women is composed of international researchers and fellows, some hailing from countries that are adversely affected by recent and current travel limitations to the USA. A sit-down interview between Jennifer Doudna and Dan Rather, one of the world’s best-known journalists for much of the last half century, evokes matters of science, but also philosophical, religious, and even political issues:

Dan Rather has also thrown his weight behind the documentary as one of its three executive producers. As sharp as ever, the 87-year-old loves science and knows that it is vital to tell the stories of science to spark conversations about these important topics. In an interview with Canadian broadcaster CBC he states, “I’ve been mightily blessed and really lucky as a journalist, I’ve covered my share of big stories. I don’t think I’ve ever covered something that has the potential to be as far-reaching and as consequential as this scientific breakthrough to do gene editing.”

The technology is still in its infancy and has lots of potential to do good but carries an inherent risk if in the wrong hands, Rather says. “We literally know, in theory, how to design babies — we now have the biological breakthrough that will allow someone to do that.” People need to start asking critical questions, he says, and there needs to be regulation. But “…if it is to be regulated, who is to do the regulating — is it the UN, individual governments? And how do you do that? This is the conversation we need to be having with ourselves right now.”

Director Adam Bolt deserves credit for his sensitive and delicate handling of a hot potato issue. He knows how to go about them. He is the editor and co-author of the Oscar-winning documentary Inside Job, for which he received the Writer’s Guild Award for Best Documentary Screenplay and was nominated for an American Cinema Editors award for Best Edited Documentary in 2011. He also won an Emmy in 2014 for his work on the Showtime documentary series Years of Living Dangerously.

David Sanchez, a teenager with sickle-cell disease, looks at a tube containing the CRISPR gene editing machinery. Clinical trials are already underway to cure the disease.

He went into the project with an open mind but was soon struck by how much debate was going on within the scientific community about how to deal with CRISPR. “For example, many scientists are genuinely unsettled by the idea that we could design our own children and think that altering future generations is a line we should never cross. But others don’t see as much of a difference between CRISPR and other technologies (space travel, modern medicine, and even agriculture) that have in some sense ‘changed what it means to be human.’ This is a realm where there are no easy answers, even to those who understand the science best.”

The team around Bolt and Rather is a veritable Who’s Who in science and TV-making, from co-executive producers Elliot Kirschner and Greg Boustead to Regina Sobel (editor/co-writer), Meredith DeSalazar (producer), Sarah Goodwin (producer and leading science writer), Derek Reich (Emmy award winning cinematographer), and Steve Tyler (Emmy Award winning documentary film editor). The company behind this documentary, Wonder Collaborative, brings innovative storytellers and the global scientific community together in a spirit of experimentation and collaboration to revolutionize science filmmaking with the wonder, awe, and diversity of discovery.

The documentary will be screened in Paris on October 26 at 2 pm at the Pariscience International Science Film Festival (107 mins, VOSTFR). Other screenings in France are currently being discussed.

![]()

Lead image and photo of David Sanchez courtesy Wonder Collaborative/Human Nature; photo of Professor Jennifer Doudna by Duncan.Hull – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link; photo of Emmanuelle Charpentier by Bianca Fioretti, Hallbauer & Fioretti – Bianca Fioretti, Hallbauer & Fioretti, copyright owned by Emmanuelle Charpentier who made it a Creative commons picture, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

Leave a Reply