Expat life in France 80 years ago changed dramatically overnight with the advent of the Second World War.

Brexit is off the front pages. A sort of phony war as the media is distracted by bikinis and burkinis. The elephant will return though, Article 50 will be triggered and negotiations will reveal the true consequences of the UK’s vote to leave the EU. Barring a complete breakdown in relations between Britain and its EU neighbours, UK residents in France will have a choice about whether to stay in their adopted homeland. Europe has at least come this far in the past seventy-five years.

In June 1940 the continent was a very different place as Britons living there were faced with the prospect of leaving their homes, businesses and lives to escape the chaos of war. My grandparents and mother, then a young girl growing up in the South of France, were part of this exodus. Hanging on until the last moment, when it became clear their only option was to flee.

They had moved to France in 1937 for reasons familiar to many Brits living there today. A fork in their lives, a fresh start and a stock market crash that put them in a financial situation more suited to rural France than London. They packed their most precious belongings into a car and headed across the channel with their one-year-old daughter.

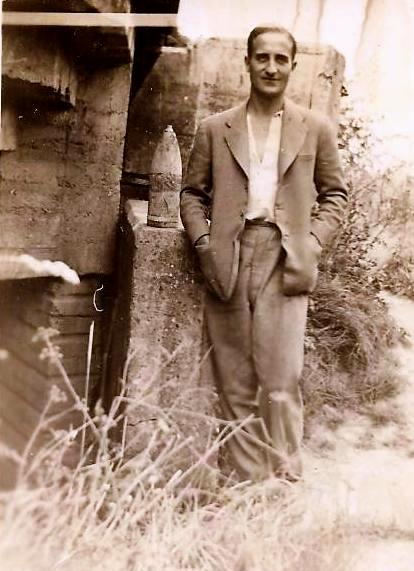

Moving to Europe in those days was of course more complicated than today. The British population of France numbered tens rather than the hundreds of thousands and there were border controls, customs and visas. France was still France, not the English speaking EU version of today. Even so, their privileged backgrounds ensured they were more prepared than most. My grandmother, Joyce, was the daughter of an England cricket captain who died when she was a child. She was sent to live with her poet uncle in a château near Dijon. Ivan (pictured left), my grandfather, grew up in pre-war Shanghai, then perhaps the most exciting city in the world. France was not a daunting step for them.

Moving to Europe in those days was of course more complicated than today. The British population of France numbered tens rather than the hundreds of thousands and there were border controls, customs and visas. France was still France, not the English speaking EU version of today. Even so, their privileged backgrounds ensured they were more prepared than most. My grandmother, Joyce, was the daughter of an England cricket captain who died when she was a child. She was sent to live with her poet uncle in a château near Dijon. Ivan (pictured left), my grandfather, grew up in pre-war Shanghai, then perhaps the most exciting city in the world. France was not a daunting step for them.

They eventually settled in the hilly countryside near Grasse above the Riviera, where they found a small farmhouse and some land. It was beautiful, simple and cheap. They spent the next three years growing everything from olives to melons and tomatoes. Ivan kept a diary which records steady progress, working alongside locals proud to call themselves ‘paysan’.

They must have felt rooted in France because when war was declared in September 1939, they carried on as if nothing had happened. Even in May 1940, as the Germans overran the French armies in the north and sent the BEF scuttling to Dunkirk, they procrastinated about leaving.

In the end, something closer to home forced their hand. A French neighbour warned them that a grief stricken farmer was roaming the area with a gun, looking to take revenge for his son killed in action near Dunkirk. The man was one of a growing number of French people who blamed the evacuating British as much as the Germans for France’s rapidly deteriorating situation. Vichy was founded on sentiments such as these. The farmer tragically took his own life but the dangers were clear and when they heard that ships were evacuating British nationals from the coast at Cannes, my grandparents decided to leave.

In Cannes they found a cross-section of the expatriate community camped out in front of the luxurious Carlton Hotel. Wealthy aristocrats from opulent villas stranded alongside tourists and British employees of local businesses. News of a possible French armistice with Germany had brought panic and confusion. There were also rumours that the British consul had bolted with the Duke of Windsor’s entourage, Mussolini’s Italians had captured nearby Menton and there were no more ships available to rescue British nationals. All of which turned out to be true.

A few days earlier, two ageing coal colliers, the SS Ashcrest and Saltersgate had left Cannes for Gibraltar with decks and holds crammed with British evacuees. Accounts of pampered expat residents ordering G&Ts and demanding to ‘be shown to their cabins’ are told alongside tales of remarkable stoicism in terrible conditions. Several people went out of their minds, ‘owing to enforced deprivation of alcohol’ according to writer Somerset Maugham, who was on board the Saltersgate.

Despite much support from locals, the remaining British nationals at the Carlton were now a source of concern and some irritation to the French authorities. The mayor of Cannes offered them a train to Marseille, where they were told there ‘might be a ship waiting’. If not, they could ‘walk to the Spanish border’, a further 200 miles away. Many of the refugees refused, but Ivan realised that to remain would almost certainly lead to internment.

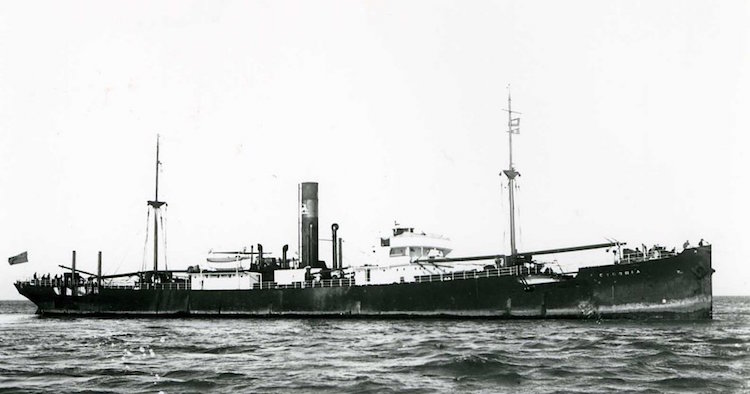

They arrived in Marseille at night, during an air raid. A terrifying experience for men, women and children as they trekked to the city’s port in search of a ship. Salvation came the next day in the rusting shape of the Cydonia, a Gibraltar bound coal collier, onto which eight hundred British and many French refugees embarked in a rainstorm. According to accounts Ivan carried an injured man on his back. He took one look at the soot-covered hold of the ship and decided it was safer to remain on deck.

Three days out of Marseille this decision was vindicated, as Joyce spotted what she thought was a ‘beautiful silver fish’ in the sea nearby. A klaxon sounded and it quickly became apparent that the ‘fish’ was the first of two approaching torpedoes. There was panic as refugees tried to grab life jackets before the ship exploded but miraculously the torpedoes missed and the Cydonia sailed on undamaged. The SS Ashcrest, which had sailed from Cannes with British nationals two days earlier, survived a similar attack.

The evacuees spent the next five days in constant fear of another attack. They reached Gibraltar on 27th June. A signal read ‘Congratulations on your escape’ and there was cheering as the creaking collier passed the Royal Navy Mediterranean fleet moored in the harbour. A few days later these powerful battleships would sail for Mers el Kébir to sink the French fleet and prevent it falling into Nazi hands. Allies turned against each other. These were sad and desperate times.

My grandparents eventually reached Plymouth on the Viceroy of India, a converted liner, carrying escaping Czech and Polish troops. They were lucky. Several people died on the ships that carried British civilians from Cannes and Marseille that June, but this paled against the thousands who lost their lives when the liner RMS Lancastria was sunk off the coast of St Nazaire in the same month. Many were ordinary men, women and children trying to escape war; similar to those risking their lives to cross the Mediterranean today. U boats, Stukas, or people smugglers. The results are the same.

Joyce (pictured above) stayed in London and drove an ambulance during the Blitz. She returned with my mother to the farm near Grasse in 1946, where she lived out the rest of her life. Ivan joined the army but was medically discharged. He worked on a farm in Berkshire and was killed in an accident there in 1942 aged 35. His ‘Brexit’ was final. The last entry in his diary, written the day before he and his family fled their home in France reads:

Sunday June 16th, 1940:

Garden looks lovely but France seems finished.

Published with permission of The Telegraph (UK) 2016

![]()

All photos courtesy Michael Fiddler

Leave a Reply