The Lebanese-Italian poetess who writes in French is the current insider tip among lovers of belletristic literature. But she has other talents, too…

Anyone who loves French or Italian poetry and keeps an eye on emerging talent has by now likely come across the name Nada Skaff. So has anyone who loves powerful statements via jewelry. Her name is traded as artistic lead currency in Italy and Lebanon but she started her professional life as a microbiologist. She keeps collecting awards, prizes, and recognitions but treads lightly, seeking out loving human relations before fame. You notice a theme of duality emerge…

Where most artists pursue a single vision with laser sharp focus, Nada Skaff is much more relaxed, letting things unfold and the dice fall as they may. That does not mean she is not determined to succeed. She is, and she does. But her ambition is spiced with a generous dose of Mediterranean savoir-vivre and a go-with-the-flow attitude.

Like her life, her writing is marked by a deep love both for her Lebanese home land and her Italian adopted country. Beirut’s timeless elegance and Naples’ fiery earthiness come together and flow into pared-down yet passionate poetry.

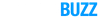

We had a chat with Nada Skaff, author of “Fleur de sel” (2013) and “Il Punto di Rugiada” (2020), to learn more about the poet and designer with a disposition for philosophical reflection and an unstoppable zest for life.

Nada, please tell us about yourself and your roots

I was born in Beirut on January 1st, 1969. At the time Beirut was a cosmopolitan and dynamic capital which for such a unique multicultural microcosm was amazingly peaceful. Until 1975, when the civil war began, the Lebanese were undoubtedly living a dream. Economic growth was constant, the city’s movida enjoyed an international reputation, the cultural effervescence allowed artists and literary figures to flock to this little Switzerland at the foot of Mount Lebanon.

The war could never extinguish the sun that bathed the coast and the peaks. Life went on, alternating as naturally as possible between tragic days and periods of calm.

My father, a lawyer at the bar, was now involved in business as the courthouse was closed. My sister and I continued our studies. Looking back, I realize that education in a good school in Beirut allows one to adapt to all the successive cultural waves of life. Resilience is taught through life’s events. The ability to consider any new cultural current enriching and fruitful can also be taught in school.

You initially studied microbiology, which is a far cry from being the artist that you are. Have you ever worked in the field?

The beginning of my university studies coincided with the last deadly events of the early 90s in Lebanon. I started a bachelor’s degree in biology followed by a master’s degree in microbiology at the American University of Beirut. The only possible career path at the time was teaching and I became a natural and physical sciences teacher at the International College of Beirut.

I often think about this change of course, but I don’t find it really incompatible. I was good at science. My early career was scientific, and I enjoyed this logical and soothing answer to the doubts in my thoughts. My love of nature had a lot to do with it. Before choosing microbiology, I wanted to study environmental health at the American University of Beirut. There were no chairs available, so I chose the most attractive of the options available. But my real calling was writing as I found out when I had the opportunity to write for the historical and now-defunct French-speaking weekly, La Revue du Liban.

What made you move from Lebanon to Italy?

When I met my husband, an Italian engineer sent to Lebanon by his company, I had already been teaching for 4 years, and I was involved in many socio-cultural events. I was already making the transition to the fascinating world of arts and literature. I went from a music festival to a book fair, eager to capture the notes and letters, anxious to transmit the passion I already felt.

My departure for Italy in 1998 with my husband, who I had married two years before, did the rest. The first thing I did in Italy was to find familiar landmarks. I enrolled at the Cervantes Centre, which I had already attended in Beirut, for courses in Spanish-American literature. There was a Spanish interlude in my life when my husband was sent to Barcelona and then to Madrid. I discovered the infinite pleasure of communicating in a language with which I had fallen in love at first sight and which has never faded since.

How did you get into jewelry design?

In 2006, having permanently settled in Italy, I embarked on a path that very quickly became an unbridled passion: the creation and production of jewelry in precious and semi-precious stones or coral. Living near Naples, in Torre del Greco, the world capital of coral, I had no trouble finding the materials I needed for my creations.

It all clicked when my husband wanted to give me a coral necklace. I embarked with aplomb – that in retrospect I find astounding – on a path that was not entirely unknown to me. My grandfather Fouad Fattal, an Armenian from Aleppo, came to Beirut in the early 1920s to found the first diamond cutting factory in the Middle East, and there I discovered their sparkling colours and mysterious, multi-faceted appearance. So jewelry was the natural path for me to follow.

The immediate success of my first collection encouraged me, and I continued to venture further, driven by the thirst and passion to combine the materials and colours that appealed to me.

Which country feels more “home” to you, Italy or Lebanon?

2006 was a pivotal year. We were on holidays in Lebanon when Israel bombed my country. Having to leave in a hurry on board an Italian military ship after left a deep impression on me. The creation of jewelry kept me busy, but I soon realised that I wanted to belong to Italy completely. I needed to embrace my new life, the world around me, and this involved a decisive action that would give an important turn to my life.

After these events of 2006, I was invaded by an anguishing loneliness. I enrolled in a degree course in French and Spanish languages and literature as if I were clinging to a lifebuoy. Salvation always comes from sources of light and hope.

The love of a language and its poets gives access to the soul of a people. I became a French teacher before I had even thought about it seriously. I woke up with the Italian workers, I actively participated in the daily swarming of people and mentalities. I became myself, alternately Beiruti or Neapolitan, Oriental or European, without worrying about being one thing more than the other. Passing on the love of a language that I knew had now became an implacable logic: I had transformed my difference into an advantage. I had taught science in Beirut, I now teach French in Italy.

And how did you then go back to writing?

I believe that reading and writing poetry is what truly heals the wounds, what allows one to dig into oneself to get the best out of it, in all humility. It is certain that art sublimates pain and that the poem sometimes transforms the mire into beauty. I am indebted to life for this love of poetry. My most beautiful jewels are probably some poems written during happy moments of inspiration. The idea is to make a poem of every piece of jewelry, and a piece of jewelry of every poem.

What inspires you to write?

“Fleur de sel” was written in a state of “poetic emergency” in 2013. I believe that poets inspire poets and fertilize their thoughts. While writing my dissertation on Nadia Tuéni, a French-speaking poet from Lebanon I was deeply shaken by this woman’s pain and her life experiences. I felt the pressing need to transcribe my thoughts. These thoughts took the form of verses, without my knowledge. Thus was born the first collection.

“Il punto di rugiada” (The Dew Point), published in Italian, contains 16 poems translated from “Fleur de sel”. The rest of the poems came naturally, in my adopted language. One is undoubtedly born a poet, but one acquires a new facet of identity as the days go by, which also asserts itself through language and poetry. The second collection was almost entirely written during the first Covid-confinement. It is the fruit of a reflection, of a journey of thought, of an awareness of the precariousness of things and of their profound essence.

Which art form are you drawn to more as you perfect your skills in both – design or writing? Why?

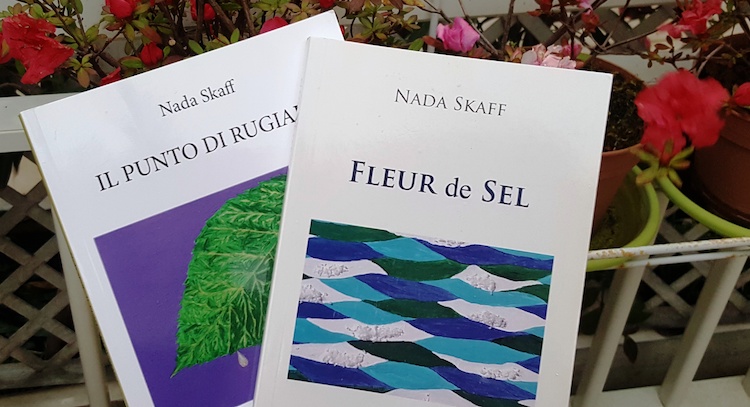

I believe that one is born with a certain way of looking at the world that allows one to observe by diluting the material contours of things and isolating their essence. Which would be like saying: you are born a poet, you don’t become one. Was I born a poet? I used to write short poems at school. And sometimes the two – writing and design – come together, like in the necklace I made using one of Nadia Tuéni’s most famous quotes, “Beirut is the last sanctuary in the East where man can still dress in light.”

You can approach all the arts you love without partitions, as if in a system of communicating vessels. You can chisel a poem like a piece of jewelry, making it radiate with a thousand facets without even noticing it. In the same way, one can create a jewel like a poem, incising poetic verses in it, sculpting a mythological scene, evoking the gods, as in the case of cameos. I strive to create unique, meaningful pieces that definitely reflect a way of being. I like the idea that as we are all unique beings, we can assert our uniqueness through our style, our choice of clothing, the wearing or abolition of an accessory. Jewelry can also be a testimony of a poetic way of perceiving the world.

At the beginning, war ravages a “land of men’s trunks” where the author no longer recognises “the green apple trees of childhood”. A plant metaphor grows in her poems, which are as simple as they are exquisite: “When the poem germinates”, the arid soil of exile will bear fruit, “soil buried in memory”. From the salt of absence will come a citrus perfume, that of the “September spray”. The word cuts the pear of bitterness in two. ”A “September rain” will nourish the dry soil of lost love, that which lays “its frail neck on the scaffold”, in this “hell of the unloved”.

In her first collection, Nada Skaff, who has glimpsed the “blinding glow” of poetry, and who defines poetry as her “ultimate chance to be”, brings together poems from every day, combining the absence of country and love with the love of country and love:“You love the islands because you are one…

I live in the land of silence and coral

When a poet is born, a flower grows on a ground covered with salt.”

— Antoine Boulat, writer, L’Orient Le Jour/L’Orient Littéraire, 2013/14

What differences and what similarities do you see between the two countries?

When I arrived in Italy in 1998 in my late twenties, I had to learn to decipher the codes that separated me from the city and its inhabitants. Everything seemed so simple and turned out to be quite complicated. I had to look to see, see to understand before I could understand the Neapolitan identity and love it to adopt it.

The Mare Nostrum unites my two countries. It is the Mediterranean that brings us together, in a permanent search for dialogue with the other. The similarities are those common to sunny countries: a pronounced gesture, the language of the body, the urgency to communicate, the will to go where the sun shines.

Street life in Naples, courtesy Jenny and Stephen

The differences become less pronounced with time: the things learned and the things that are missing from the heart and body. The people of the Mezzogiorno – Southern Italy – taught me to go beyond physical appearances and to accept differences in character. Yes, I do say “Mezzogiorno”. Democratic thought is often thought, but it really exists before it becomes a project or is translated into action. I have often perceived a great generosity in the acceptance of differences. What is missing is a greater knowledge of these same differences. It is certainly necessary to welcome and help, but it would also be necessary to know the culture of the other more deeply before pigeonholing them.

It would seem paradoxical to say: the people of the Mezzogiorno are always kind and well-disposed towards foreigners, but they would tend to look at the other person with a preconceived idea of their origin and culture. And yet this would be true. The West ignores the everyday Eastern miracle. I cannot forget where I come from. I carry within me an experience that emerges in my gestures, my choices, my thoughts. I do not fear the other, since my destiny and my childhood have taught me that it is perfectly possible to live together with religious and cultural differences in a spirit of benevolence and respect.

galeoni trasportando oli e vini,

biremi da guerre levantine,

Creta e Bisanzio fusi

nel medesimo crogiolo di civiltà.

Amico mio, piedra de ijada spagnola,

sassolino delle viscere del mare,

abbiamo osservato il Mediterraneo da levante, seguendo la prospettiva retta dell’astro d’oro.

Solo il mare nostrum ne spegneva il fuoco,

e restituiva la pace,

dialogando nella freschezza dei tramonti.

Nascere con la rete di Penelope tra le rive

e finalmente intrappolare il prezioso tempo.

Essere Mediterraneo è, dunque, questo.”

galleons carrying oils and wines,

biremes from Levantine wars,

Crete and Byzantium fused

in the same crucible of civilisation.

My friend, Spanish jade,

pebble from the bowels of the sea,

we observed the Mediterranean from the east, following the straight perspective of the golden star.

Only the mare nostrum extinguished its fire,

and restored peace,

conversing in the freshness of the sunsets.

To be born with Penelope’s net between the shores

and finally trapping the precious time.

This is what it means to be Mediterranean”.

Nada Skaff, “Il Punto di Rugiada”

What I miss about my country are the transitions from one season to another. Lebanon’s spring has a foretaste of summer, its autumn is an overwhelming attachment to the beauty of the beautiful season. I also miss the resilience of the people of my country, their endearing and so elegant way of receiving and giving, the kindness, the hospitality, the gastronomy, the fusion of languages, the landscapes, the peaks and the coast, this way of making the extremes cohabit in the most natural way in such a small territory is genius.

I try not to hide our weaknesses: the lack of integrity of the majority of our politicians, the corruption that undermines the foundations of a country and corrodes reasoning, the lack of hope… what happened in Lebanon on August 4, 2020 – the complete destruction of the port, the disfigurement of my city, the omnipresent pain, all of this remains in us like a gaping wound that cannot heal. Evil is everywhere and yet the Lebanese get up, wash, clear their windows and smile at the sunshine that warms them. I am my people. I am constantly and tirelessly Beirut.

It is also for that reason that I support Lebanese women in need by donating the profits from “Il Punto di rugiada” to the non-profit organization “La voix de la femme libanaise“. It seems like Beirut needs a helping hand during these critical moments more than ever.

How do you know the Syrian-French poet Dr. Khaled Youssef who also featured one of your works in his poetry books and prefaced your most recent book Nusa?

It was a chance meeting through Facebook where Khaled Youssef and I became friends. Khaled’s friendship is one that gives hope for a better world. I believe he is also one of the most intelligent people I have ever met. With his extreme tact, his benevolence towards all beings, his ability to defuse any conflict, his sense of humour, his ability to make his adopted cultures and languages his own, his generosity and his readiness to share, Khaled is a being who sees the essential and goes there without loss of energy, extremely positive and quick-witted. We haven’t seen each other much, but that’s how I see him, and I don’t think I’m wrong at all in making this judgment.

Among the awards you have received for your work, which one means the most to you and why?

I was published and read, which is the best answer to my dreams. Some of the articles written have particularly moved me. A poem breaks the circle of solitude and withdrawal. The poem is the reward.

But just now – in April 2021 – I am very proud to have won the Yolaine et Stephen Blanchard Poetry Award for my new collection “Nusa” which will be published shortly.

How do you live and experience this current difficult time? What makes you carry on every day?

It is the love of life and the journey that allows us to continue the journey we are allowed to take. The gift of life is a mysterious, fabulous gift. So much exploration and silent discovery in such a short time. And then I was born in a land where deep roots will undoubtedly allow me to grow up well, and why not, to age well. I still have hope. I love to walk. I walk for miles every day in my hometown, and I take the time to observe the looks, the flowers, the Italian landscapes, the bell towers, the frescos. Everything amazes me.

As the mother of two children, what do you make of today’s society? Do we still have a chance to turn things around? What needs to happen to do so?

My son Enzo Manuel will be 23 years in May 2021, my daughter Anna Sara is 21 years. Their first names, by the way, also constitute the anagram of Mansara, my jewelry company. They are hard-working students with a critical mind, beautiful people, interested in the world, in nature and in art. My son is finishing his studies in computer engineering and composes music for movies that he just posts on Youtube. My daughter is studying political science. She loves reading, music and movies. I like the coherence and intellectual honesty of my children.

When I came to Europe, I couldn’t help but notice the difference between Italian and Lebanese teenagers. I was more used to the shy deference of the latter. But evil is global. An entire generation has projected its dreams of greatness onto its offspring. The process that engages effort, merit, and the joy of achieving one’s goal in the child is often short-circuited.

I don’t know if I myself have been able to convey what I preach. I am fortunate to work in Italian schools as I teach French. My own experience in middle school made me realize that children are still capable of dreaming. It is the adult example that distorts the situation. Rigor and discipline are words that frighten and yet respect for others and for nature goes through self-respect. Everything becomes so much easier afterwards. The whole world needs to set the record straight.

What message do you want to share with our readers?

I would like to share what makes me happy every day: creating a project, cherishing a dream and trying to achieve it with all my soul. Getting to know and accept yourself is also very important, as well as getting your thoughts in order and setting priorities. Every goal achieved, no matter how trivial, makes you happy. My next big project is publishing a novel. I would like for poetry to never desert me. I would like to make the people around me happy. There is no time to lose. Let’s live.

Follow Nada Skaff on social media:

Poetry: Facebook

Jewelry: Facebook

Instagram: mansaracult

All photos courtesy of Nada Skaff unless otherwise credited; photo of Martyrs’ Square 1985 by James Case from Philadelphia, Mississippi, U.S.A. – Peace, CC BY 2.0,

Leave a Reply