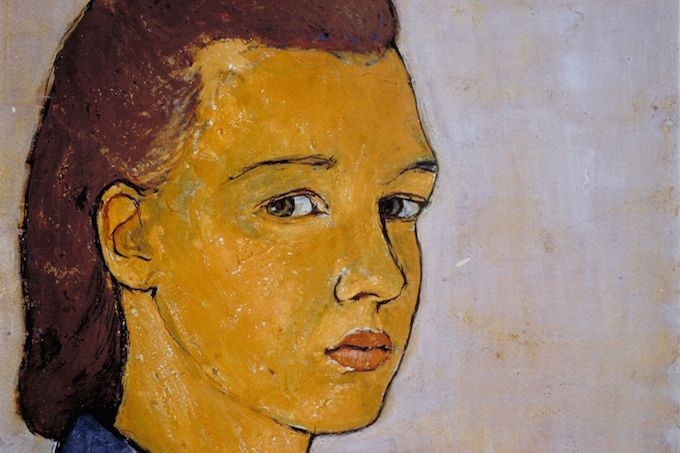

German artist Charlotte Salomon created her greatest work whilst living on the French Riviera, before being deported to her death in Auschwitz.

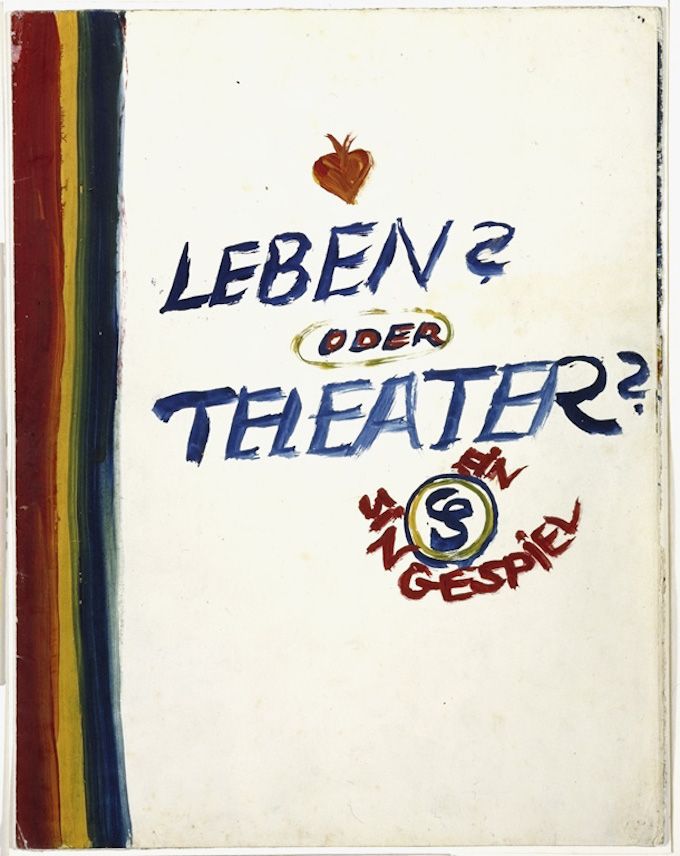

Last Wednesday, popular author David Foenkinos was awarded the Renaudot, probably France’s most prestigious literary prize after the Goncourt, for his latest book, Charlotte, which recounts the real life story of painter Charlotte Salomon. A perfect occasion to discover, or rediscover, the tragic tale of this young German artist who created her original and compelling artwork, Life? Or Theater? An Operetta, right here on the French Riviera, while living as a refugee from Nazism.

Structured like a play and comprising various scenes, dialogues and musical references, this massive work is a testament to Salomon’s unique artistic vision but also to her life, which started on the 16th of April, 1917 in Berlin. Born to Albert Salomon, a surgeon, and Fränze Grunwald, she was, despite her father’s reluctance, named after her deceased aunt. When she was only nine, Charlotte’s mother committed suicide — in order to protect her from her maternal family’s terrible secret, the little girl was told that she had died of influenza.

After the Nazis came to power in 1933, the young Charlotte had to drop out from school. She still managed however to get admitted a few years later to the prestigious State Art Academy in Berlin which only allowed 1.5% of Jews. This is during that time that she met and fell in love with Alfred Wolfson, a Jewish musician twice her age, who became the first person to believe in her. But then came the Kristallnacht in 1938, and Charlotte was sent to live with her maternal grandparents who had found refuge in a beautiful villa, l’Ermitage located in Villefranche, at the invitation of Ottilie Moore, a wealthy American of German origin.

The reprieve did not last long. Soon after she arrived, her grandmother committed suicide in 1940 and Charlotte finally learned the awful truth that had long been hidden from her, that eight other members of her family, including her mother and aunt, had also taken their own lives. Terribly distraught and convinced she would be next, the young woman then decided to break the vicious circle and “to paint her life rather than to take it.” To do so, she moved to Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat and in the gardens of the Hôtel Belle Aurore, overlooking the Mediterranean, she started working of her masterpiece. In the space of two years, the young artist produced more than 1,370 notebook-size gouache paintings – only 795 were kept for the final version – with bright colours used to recount her early life, gradually darkening as the story moved along. To coordinate the various drawings, she included dialogues, at times witty, ironic or sad, to introduce the characters, scenes and situations, as well as some music, both classical (Schubert, Bizet…) and popular (famous German songs), anthems and even prayers. The project was finished in 1942 and if it may have been intended as a diary, the final result is first and foremost a spectacular and deeply moving piece of art.

In one of the latest captions accompanying her paintings, Charlotte wrote “I will live my life for them all.” She unfortunately never had the time. In September 1943, the Italians, who until then had occupied the south of France, surrendered and the Germans moved into Nice. Soon thereafter, Nazi war criminal Alois Brunner, a top aide to Adolf Eichmann, started organizing some of the war’s most violent raids and on September 24th, 1943, Charlotte and her husband were arrested in Villefranche. Deported to Auschwitz, Charlotte who was four-months pregnant, was immediately sent to her death.

Her short legacy however did survive. Probably feeling that she was in danger, Charlotte had managed to entrust her work to her physician and friend, Dr. Moridis of Villefranche. “Keep this safe. It is my whole life,” shortly after finishing it. Dedicated to Ottilie Moore, it was donated to the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam by Charlotte’s father and stepmother after the war.

Lead image Charlotte S“ von Charlotte Salomon – Museum page. Lizenziert unter Public domain über Wikimedia Commons; Book cover “Charlotte Salomon – JHM 4155“ von Charlotte Salomon – Museum page. Lizenziert unter Public domain über Wikimedia Commons; Photo of Plaque by OTFW, Berlin (Self-photographed) [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Leave a Reply